Craig Powell, Music and Women’s Bodies

Five Islands Press, Wollongong, 2002, 68pp

ISBN 0 864187769

RRP $26.

A review by Rebecca Kylie Law

In admiration of Powell’s poetic oeuvre, I reached out to him recently via email unaware an accident of 2010 had left him brain-damaged and crippled. My enquiry asked if he would consider contributing some comments towards my new, forthcoming collection of poetry with Wipf & Stock. He wrote back to express his regret at being unable to accomplish such a task but was flattered that he had been considered. Mortified by the news and the gall of my proposal, I quickly wrote back a letter of apology. Yet Powell persisted in making things well again, writing again and again with anecdotes of his poetic life, of insights into what was fast becoming a succinct biography of his life. We exchanged books and on receipt of Music and Women’s Bodies I was so stirred by its beauty that I approached Powell for the permission to write a review. It was granted and this is the product: for Powell and eternally, his readers.

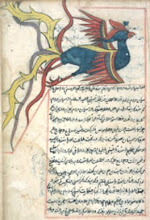

There is something heavy, dark and immense in the early pages of this collection and like a world it shifts its weight to sleep with the moon or grow under the sun. True to its cover image “Artist and the Muse (Rembrandt)” by Gary Shead, Craig Powell’s Music and Women’s Bodies seems inspired by a wooden doll-like female marquette of a real women, shy to the light, sweet to the knowledge of touch and brave to the new. Just as Shead’s doll comes forward out of the shadows, her hand touching the side of a supposed artist’s easel, Powell’s poems reveal truths of love that seem so honest they could be majestic – indeed, the doll’s dress is majestic in the silkiness of the fabric, the tones of lavender purples, smudged pastel pinks and moon dusted whites. Her silver drop earring adding class to her exposed shoulders and arms. The picture and the poetry collection speak of the same muse, that drifting presence of the beloved that is sometimes hiding but inexplicably devoted. This is the slowness that anchors Powell’s poems although the gaze is unapologetically male.

Born in Wollongong, Powell’s male gaze finds its place in a rural landscape fraught with opposites, life versus death, pain versus happiness, the visible versus the invisible. So that, visiting his brother’s dairy farm in the first poem “The Calves”, Powell is witness to an experience he can never bodily know and the atmosphere is tense with pragmaticism and empathy. It is October and in “the paddocks one/by one the nubbly shadows stagger up from/ the soil” and calves are born of their “Ayreshire/ mothers”. Two days later, in the “wooden feeding pens”, there is a mess of life as the vigorous newborns clamour for the milk of “the whole herd, a blind blurring of mothers” poured out in buckets; whilst out of “the spring light”, on the “earthen floor of the barn”, his brother’s daughter “holds a bottle to a calf too frail to suck” and cradles it to its end. “She’ll keep cradling it”, announces Powell, asserting the maleness of his gaze and the marvel of the opposite sex. Yet the pain doesn’t stop there, the mother cows in the closing stanza crying “noisily for the calves taken away” into the evening whilst inside the house, the human family share “wine” and “a meal of male calf”. Powell’s gaze, pragmatic and empathetic empties itself into the landscape of his surrounds, gazing out at a moon rising behind a distant hill and drinking in its outpouring of light – “white as the ash of ancestors”. A communion of sorts, the timeline from birth to midnight and the end of the day is newly recognised by the late hour of their meal and the exaltation of the moon so that “they eat more slowly”.

There are four sections to Music and Women’s Bodies and the division considers the same landscape from different vantage points. In Section I, Powell is child and man, brother and grandson, son and nephew, husband with wife and in these guises is always the non-judgemental watcher, the human with feelings who suspects right and wrong but is never an outsider of a group experience. When a child, in “Die Zauberflote” for instance, he plays a tune about a “bird-man” wanting “a maiden or little wife” and announces only “grown-ups…/ knew about things like that”, deciding later in the verse, he wants “not to know”, for the world instead to be made up of fiction, of “stories”. Recognising difference, the “grown-ups” are still the same people that “take me home with them” and in this way, Powell unifies with the family unit. In Section II, Powell leaves the present landscape of his own birthing, youth and adulthood to visit the landscape of his father in c.1912 and 1922.. He describes the Australian landscape his father is born into, the disputes between Aboriginals, an Afro-American working for a “Chinese Market gardener AhSoon, known as ‘Smiler’ and police. There are violent mobbings and deaths not only racial but also territorial as Powell tells us in the end notes of the collection: “local aborigines were kept out of town and not allowed to camp on Crown land”. The two poems here, wedged between Section I and Section III become the understory of the first incarnation of Powell’s existence and the third incarnation of Powell’s existence as a poet and orator of difference, otherness and truths. Translating select poems of Sydney-based Russian migrant Yuriy Mikhailik, Powell fills the pages of Section III with a sense of a universal pastoral dreaming. So that the gaze of Milhailik across the Australian landscape meets the gaze of Australian born Powell and nature, event and human sentiment are non-conflictual: “the moon glares in my eye, it scorches my heart,/ it chills memory”. There are “Hay-stacks… quiet/ where the sky’s edge is found” and “the evening star” dances “over the world’ as if it is “forever”. Section four becomes then, a celebration of “coming back” from the “world” to the place of childhood; and only then, being the adult with a past. Replete with memories of past girlfriends, the loss of a child, a rat surfacing to the sun from a basement, Music and Women’s Bodies is a child’s drawing of relationships between image, fact and music. Hearing music from the radio his Aunt tells him is Tchaikovsky, a boy peers out of her lap to better espy her newspaper and a “lingerie ad” of “a woman in a petticoat” as “he’d once seen his mother”. Yet the adult Powell, imagining this scenario is smiling “at the boy” and his confusion and acknowledging what can be known is sometimes: “Just that, maybe. All he held against death./ Music and Women’s bodies. Just that.”

Concluding with the poem “Garden Spiders”, Powell’s journey across the vast landscape of his mind, heart and soul fixes on a garden time has left to grow wild, on a garden which “becomes truthful, a green/ wildness with no lawn or flower-beds”. And although Powell has told us earlier in “All you Know” that there is no God, the spiders in this honest garden are “angels” or “garden sprites” or even “the ghosts of ancestors” and that dark, heavy immensity of our world is given the breath to suppose it unfathomable. Which is, more exactly, Powell’s majestic muse, his opposite attraction; and that which brings the music of love but can never be known like the word.

- © Rebecca Kylie Law 2020

Rebecca Kylie Law holds a PhD from UWS. She has published five collections of poetry with Picaro Press, Interactive Publications and Ginninderra Press and another is forthcoming with Wipf & Stock. Individual poems, reviews, interviews and articles have been published in numerous journals Australia and overseas. She works as a freelance writer and teacher.

1 comment:

It is with sadness that I write that my father, Craig Powell passed away on 29 August. He passed away quietly in his sleep. He had been in Aged care for the last 16 months of his life, though my brother and I had modifications made to the house, in hopes we would be able to bring him home. Due to construction shutdown during Sydney covid restrictions in 2021, the modifications were not completed until 2022. Various hospital visits further delayed his move from aged care to home, though my brother and I were able to visit him in aged care in the last days of his life.

Craig’s funeral will be held at the East Chapel of Northern Suburbs Crematorium, on Wednesday, 21 September, at 1:30 pm.

Post a Comment