You should never lend your tools to Pistoa. They will be returned broken like the smiles of the unsuspecting, and not because he is a bad man, or at least no better or worse than most, but because he is what the old crones would call distracted. I often pass him on the road between Dragon Pass and the old Venetian watchtower, his great bulk hurling its shadow down the precipice. There is something oddly effeminate in his walk, a maiden’s swirl of the hips when he thinks the world has its back to him, that massive weight pressed down on the very tips of those tapering, hairless toes. Pistoa does not sing or rain down curses on the world like most forced to ply their trade along this desolate road, but walks silent and heavy-lidded as though lulled by the whisper of his own girlish footfalls.

I wrestle with the same conflicting emotions whenever I encounter him like this, for we are well enough acquainted to know that he cannot abide me and yet not well enough for me to be certain of anything more than the gentlest rumours of his provenance. I honestly believe he toys with me a little, knowing he has the better of me in this regard, but perhaps he is like that with everyone, turning each day on its head with a yellow leer.

*

In what remains of my village smouldering on the wrong side of the Appenines (now dubbed somewhat cruelly “The Jade Terrace”), I was known as “the priest”. Why? Because I was taught the rudiments of reading and penmanship by a beet-faced mendicant who became a little too fond of my sister and who was left dangling from a gibbet until his flesh fell away into the oily pond of crows. Euclid came later, as did the revelation that my sister was in fact my cousin and that my father was in fact my uncle. It was my first lesson in how quickly the world can be turned on its head, a fact somehow encapsulated in Pistoa’s yellow leer.

When this nickname of mine reached Pistoa’s ears, how or by whom, I am still not certain. We are a strange community of solitaries passing each other on the road with our sacks of tools trading greetings and rumours of jobs and occasionally to be found in a dissolute swarm where it remains to Pistoa, the most sullen and illiterate of us all, to apply the finishing touches to our stones, whistling a steely tune as he turns a dead weight into a living thing.

“Bless this priest,” he has burred more than once as he returns me a twisted chisel.

*

It is not just for his gruff manners or his delicate hands that Pistoa is singled out by this strange fraternity of ours.

Since the Emperor and all the great Princes of Europe rode east never to be seen again, we who remain have had to find work wherever we can. The Chinese understand this and are happy to leave us free to ply our trade. City walls need constant ballasting, rotten struts replaced, stones cut for the old Roman roads. They have the same worries in the east. Cathedrals continue to rise from the charred allotments, but most of the money raised to build them now goes to Samarkand to be counted, and the Chinese are a very slow and deliberate people. They cannot understand why our places of worship need to be quite so capacious, or indeed why we should risk our lives and civic fortunes fashioning them out of stone. Yet my kind must fight our way through the same ragged hordes, chattering and laughing in Chinese, Tuscan, or Lombard it doesn’t much matter for it is always over the shriek of the saw or the sharp echo of the hammer.

*

The few Chinese I have discussed the matter with agree there is a heaven, only theirs appears to have no God in it. What point, then, trying to reach it with our spires? They talk like Pistoa walks, smirking and heavy-lidded as though our language tickled their throats. But unlike them, Pistoa cannot forgive a slight, no matter how abstruse. He is one of those who talks of rebuilding Milan, often when he is drunk on rice wine.

*

In Arezzo even now every man’s cousin is every other man’s apprentice. Pistoa is no exception, and when work is slack I lodge in his cousin’s old room in the house of Master Cano off the Carnival. The road has its own serendipity.

The address is not to Pistoa’s taste, for to he and many like him the Carnival is not some harmless if rather ubiquitous distraction but a subtle tool of subjugation worthy of priests and Ghibellines.

“Only a fool whistles at dragons,” he spat at me once through the haze and steam of their pipes and rice wine and the ducks basting to a warm terracotta while they exhorted us with their hands held in prayer to please cut off a slice.

*

If I seem to welcome these admonishments of his with an involuntary grin, it is because of the stories that follow Pistoa wherever he goes, as stories do the solitary. They buzz around some men like flies. That he has been to Samarkand and worked there on the Prefect’s palace. That he has ventured even further east to view the great sarcophagus that houses the bones of the Emperor, seen the tattered Valois standard flapping in the dry silence. The mountain of Mongol skulls. That he returned fluent in the harsh language of the Chinese and comfortable with their ways. I believe these stories because they explain the strange expanse in his speech, the odd gestures, and I have seen him carousing with the off-duty sentries night after night. But I am yet to get to the bottom of his contempt for the Carnival, only that my love of it seems to reinforce his dark suspicion of all that exists.

*

Now and then, because we both appear to have no family or friends, I will follow some vague, sunstruck, weary gesture of Pistoa’s toward an inn where we slump amidst a drunk and tired rabble of sentries and Lombard whores, and he will gaze at me as though at some shape in the mist while I ask him with my eyes if not with my tongue what is all this that has suddenly befallen us? Where does it come from and what does it mean?

“This table is your home, priest,” he softly cupped the air between us last year in Ravenna that week of the crow clouds, before staggering off to the dice games in the corner where the chickens flap and die and he will dare the drunken sentries to bet their swords on a throw. More than once the captain of the watch has locked him up for doing this, but sometimes I think this suits Pistoa who has never been so sure of a roof over his head as a man with a sister for a cousin and an uncle for a father.

*

In the house of Master Cano reigns an air of perpetual disquiet, as though something had arrived at the door one morning that no-one could quite put a name to. When the Chinese first knocked on the gates of our towns and cities, tired and bemused as we at the size of the world, two old soldiers were billeted in my very room. That was a long time ago. But like them I still find myself drawn back to this house and Master Cano with his foul mouth and soft voice and that sense of something lurking behind the fire. Pistoa spits whenever I mention it. But time here seems to pass like time was intent on passing when I was a child. As shapes rather than a line or the perfect circle of the Chinese. All different kinds of shapes, some familiar, some decidedly odd. Anyway, Pistoa spits at almost everything I say.

The girl who lives with Master Cano is very much in love with Pistoa. He cannot bear to hear this, but it is true nevertheless. I am nothing to her, worse than nothing for I make more work for her, except when I mention that I have seen Pistoa. Then she rushes to me, pats my shoulder and plies me with drink. Old Cano calls her his daughter, but she is not his daughter. There is no glint in his eye when he talks of her, merely a dark brooding, a kind of welcome shadow from the glare of the sun. Rumour has it she simply appeared one day, there in the attic room, dressed in a man’s costume with buttons down the front and barking incoherently into a tiny box that feels like soapstone to the touch. She speaks a strange dialect that seems to dart like needles from her mouth. Sometimes that tiny box of hers will make a whirring noise like pigeons in the eaves, but it must be rusty for it never seems to finish its cogitations to the girl’s satisfaction, although it did make her some money for a time at the Carnival. She is a lazy, foul-mouthed girl of twenty who is constantly complaining and raining down curses on Arezzo and all its people both great and humble. That we still queue for water at the Bishop’s fountain, for instance, or that we fix our hours by the motion of the sun as though Euclid were her uncle. She howled out once when the novelty of her whirring box had worn off on the crowds at the Carnival that she envied the Chinese their short walk home, and old Cano laughed so long and loud he made the embers crackle in the fire.

She calls herself Rosa, and it is obvious to me that she has never worked on the land, because she gets her seasons all blurred like a child’s matins. Old Cano thinks me pedantic, and perhaps I am, but I have never in all my travels through these strange times encountered someone quite so at odds with the world. There was a time not so long ago when Rosa may very well have been brought before the Bishop, but the Chinese have put a stop to all that after the Prefect’s report on the last burnings in Milan filtered back to Samarkand.

“Ah priest, she is only a girl!” is Master Cano’s stock reply to my misgivings about Rosa. For as far as the old man is concerned, the Chinese have outlawed the devil.

*

When Master Cano speaks about Rosa’s mother late at night, drunk in that chair he never seems to leave, I know he is lying but I let him go on with his fabulous tales of love and loss and love regained because the telling seems to assuage some terrible need in him. That is the other reason I am known as “The Priest”, for I am easily waylaid. There is no doubt in my mind or anyone else’s that Rosa loves the old man, but that does not stop her leaving him alone for hours, sometimes days at a time while she cavorts with those harpies in the Piazza Grande. There is such a shine on her face when she returns, however, to find him just where she left him that I can’t help thinking he is her anchor in a very wide Sargasso. It is a shore I have sat on. But her relief soon enough turns to the usual howling and breast-beating about the idiots who surround her and the stench that rises from us all as though the flesh had already left our bones.

*

For all their appreciation of our work, the old soldiers’ breathless lionising of the craft of men like Pistoa, caressing his dedications to the Virgin with their rough peasants’ hands, the Chinese have no need for us east of the Appenines. It was there, in my home, that the Mongols found themselves funneled between the mountains and the sea, and where as a consequence they wreaked their most horrific devastation. I am one of those, like Rosa, who has watched his life vanish before his eyes. It was there the Chinese finally caught up with their wayward cousins after pursuing them halfway across the world, and where, according to one old soldier who lodged with Master Cano, so deafening was the clash of metal on metal it brought the snow down off the mountains. Now the Mongols have vanished like a terrible mist, and the Chinese have no shortage of men to guard the mountain passes from round prying eyes. Even the meanest of goat tracks are peppered with their eerie hessian tents, bunched at the lip of the ridge east or west depending on the season, almost as though they had decided to retire their ageing auxiliaries this way, eking out a living in the mountains that shadowed my childhood with the sorry remnants of the Mongol herds.

*

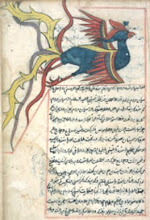

The little creature has eyes the colour of moss on a keystone. Lifeless, if you look at it a certain way, and the piercing cold of little things. It seems trapped in its tiny body. Pleading with us with a scratch of song, its stiff little wings flapping like the corners of the old man’s mouth who holds it on a string. Whirrs and preens as it jumps through hoops, the little string a mystery, a straight line through a circle, then settles down stiffly again on its bright copper perch. The old man then invites all and sundry to lift the rope and run our hands over its stiff little body, but that is the realm of children, and their expressions always seem a mixture of disgust and puzzlement. I can never decide whether at the man or the bird.

I lay no claim to posterity in writing down what I see and hear, for I have learnt that the senses can only be trusted as far as reason holds them to account. Thus by putting these things into words I hope to see them more clearly. For the world seems to me to be full of dark shapes perpetually hovering in the corner of my eye. Perhaps, as Master Cano insists, they have always been there. Plato said as much, but I cannot account for what Plato saw in the Attic light of long memory, only that these shapes seem to demand my attention. And so I will commit them and their strange world to parchment, in the hope that by doing so I will bring us all a little closer to the world of light and reason.

I have entrusted these pages to Master Cano who is my sole confidante in this life and who tells me of a loose board in my room that will accommodate them quite happily. The Chinese may have outlawed the devil, but old habits die hard and he shows no interest at all in what I am doing. It was not so long ago, after all, that words could kill a man. He is wise in his own way, but a head so crammed begins to unburden itself as it begins the slow ascent to heaven, so I am happy he does not ask too many questions. For there is something about the way that girl Rosa looks at me that reminds me of those dark shapes in the corner of my eye. As though she were awaiting my answer to a question she had not yet mustered the courage to ask.

*

When spring finally arrives we are called away to clear the rubble in Parma. Needless to say it is back-breaking work at the behest of the local Captain, a leather-faced Turk with notoriously deep pockets who grows sheepish when he learns who we are. He explains that his soldiers are too old, and with a measure of deference he feeds and clothes us and lines our pockets when we are done. Even Pistoa is touched by the care the Chinese take with the dead and the maimed. Once the rubble has been cleared we dig down into the cold coughing loam, but we can find no evidence of subsidence. It is just like before, in Prato and Firenze, as though the buildings had been buffeted by a powerful gale.

On my return to Arezzo, Master Cano tells me of other such incidents across the mountains, which would explain the sudden ageing of the local garrisons. He holds out a grey box to me and asks me to rub my hand over it. The surface is smooth as soapstone, much like Rosa’s little box. The old man tells me my room is full of these objects, and I go up to find them neatly stacked by the window, a hundred or more grey and placid as a lake except where the pigeons have been. He tells me Rosa knows something but is not telling and when pressed left the house in a storm.