Lest we Forget

Our friends......

Sunday, April 25, 2010

Friday, April 16, 2010

New Poetry by Benjamin Dodds

Archibald’s Fountain

After the washout,

we were so wet it was stupid.

We didn’t even get an overture

before dawdling out

into the darkening evening

with the rest of the cackling crowd.

Three or four islands of friends sat hopefully

on the drenched Domain lawn,

quietly fooling themselves.

If ever there was an event

to be cancelled for rain,

this was it.

I smiled at new families and old friends,

all out for a night of free arias in the open air,

all soaked to the bone now.

But nobody ran.

You can’t get wetter than drenched.

It was Sydney in summer

and no-one was cold.

As we crossed the road back into the park,

I conjured an image:

a silently packed Opera House theatre,

the audience wearing their best

as the roof hinges open

and the rain comes down.

Corporate-sponsored programmes

curl around hands like wilting posies.

That night we swam

in the fountain

in the park

with the Greek gods

and a goddess

and a bronze turtle.

Today I dug up a photo;

I’m wearing a white plastic sheet,

Jesus sandals

and the dripping rictus of a smile.

I think it’s Theseus

whose bronze scrotum

I cup in my hand.

I only remember this night

and this photo

because of Alison Clark

and her poem

about these same sculpted figures.

She has dusted off this stupid image

of my wet and juvenile self.

- Benjamin Dodds 2010

For more info on Benjamin simply click the post heading.

Wednesday, April 14, 2010

New Poetry by Ashley Capes

gatefold sleeves

the oarsmen shout

and the crash of waves

echo in their mouths

through so much black

the moon drops closer

for a better look

their buttons taste like salt

and the bunch of muscles

reminds me of my father

working with his saw

at home mum is cooking

playing Hawkwind while

I look at the LP, discovering

gatefold sleeves

the boat rolls around and

across parts of the water

their gifts are reflected.

- Ashley Capes 2010

Tuesday, April 13, 2010

New Poetry by Stuart Barnes

MIRAGE

Dionysus (is) the Master of Illusions, who could make a vine grow out

of a ship’s plank, and in general enable his votaries to see the world as the world’s not

E.R. Dodds

of a ship’s plank, and in general enable his votaries to see the world as the world’s not

E.R. Dodds

… and after the event – dust motes round and brown as rabbit dung, a tongue like

a feral cat’s in my ears, the metallic black spider scraping its fangs against

the cracked and peeling wall (for thy sweet love remembered such wealth brings

that then I scorn to change my place with kings) – and after the dawn –

apocalyptic eye of heaven, Seven Sisters dimming like Technicolor images of

childhood, blazing Botticelli clouds in a perfect eggshell blue sky (a death

and a resurrection breaking with the everyday change of light) – and after the quest –

no change for a cab, kilometers of sooty footpath on legs as wobbly and slimy

as a newborn lamb’s, zombie hands grabbing at hopelessness (the scared septuagenarians

scuttle away muttering ‘filthy junkie’ under their blue-blooded breath), a moment’s rest

at a rose garden to admire the pearly patina on a drop of dew on a leaf (so

strange the things you’ll do when you’ve had a man shriek hell across your back) – and

after the attempt – honk, whoosh, the rusty track, a landslide of malign rocks ahead

and beautiful green at my back, the chain link a fence between me and certain death –

I stood at the head of our bed and pawed at your pillow and clawed at your face

and cried ‘I’ve been raped’ and you stared at me with your ice-blue Great White eyes

and replied ‘You’re a liar’ and I came to realize the last twelve months of our

life – morning coffee (extra sweet), Eurythmics cranked in the fire engine red Alfa,

days spent combing the sands at Honeymoon Bay for shells of Tasmanian giant

crabs, evenings huddled happy as albatrosses around candles, Japanese and wine –

had all been one big Bacchanalian lie …

- Stuart Barnes 2010

(Quotation: lines from Sonnet 29 by William Shakespeare)

Tuesday, April 06, 2010

Monday, April 05, 2010

The Carnival (Third Instalment)

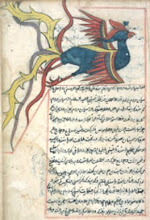

The Carnival at Perugia is a rather dull affair. The Bishop will only condone so much competition for his whores, and the local children only visit it at night to rattle the cages. It is more a collection of tepid curios, such as the two-headed kitten, or the talking bird. It has had a number of homes but is at present positioned adjacent to the torturous trickle of the Fontana Maggiore.

Perugia would appear to be a town after Pistoa’s heart. The Carnival here is overseen by two wizened old Tajiks with smiles like cuts who seem to pass their days tapping at the rows of bamboo cages in a vain attempt to raise a sullen growl from the mangy, wall-eyed occupants. That the Bishop condones this travesty at all is only due to the fact that now and then one of those strange creatures arrives from the steppes, each one a little bigger and more horrid than the last, to pique his much-lauded scientific curiosity and perhaps arouse the fleeting interest of the townsmen.

I know of only two other towns whose garrisons have allowed these creatures inside their walls – Lucca and Spoleto – and neither town has fared well by it. The hideous spectacle of these creatures, the lurid tales of them tearing entire caravans to shreds on the Magyar plains, attracts a gawking rabble from miles around, and inevitably some village simpleton will be goaded into lifting the latch on one of these ferocious, terrified things, with horrific results, especially at Spoleto, where it was said the streets ran red for days.

The Bishop at Perugia takes no such risks with his congregation and has pulled many strings with the Chinese to have their local armourers forge a steel cage that he has hoisted twenty yards above the square whenever one of these pit-eyed, hapless things happens his way. One must always consider the sergeant of the watch. From there the only danger the creature poses is if some drunken soul trying to evade the watch happens to pass under it as it is voiding, for I hear its waste can scald the flesh like lime.

We have been asked to look over the pinions and rigging, and also to satisfy ourselves as to the integrity of the iron bars against which the last of these creatures beat its brains out. For it is rumoured that the town burghers have paid for another one to be brought inside the walls to deal with the dogs. As journeymen we hear nothing but rumours.

It is rumoured, for instance, that they cannot abide closed spaces and will not cross a threshold if there are more than three candles burning inside. But such knowledge, if knowledge it is, must have been acquired through the most arduous system of trial and error, and I for one would not like to test the theory.

*

The Chinese will not let us leave until we have been paid. It seemed an oppressive system at first, and one that seemed to single out journeymen, but over time we have all learnt to see the sense in it. If we are not paid, then we cannot produce the receipts that are our pass out of the gates. And if we cannot leave the town, then we soon become a burden until the required payment and receipt is forthcoming. Our kind do not bring any more coins into a town than we can leave with. At the gate, of course, the Chinese take their cut, but who would begrudge them such a tax for such a service? They too issue a receipt. In fact my bag is a clatter of these little chits like the footsteps of my life.

For all that, the Bishop cannot be found and we must wait while someone finds him, for he is a busy man and his whores, too, must have their chits. At the hour appointed by one of his minions I wait by the Cathedral steps along with young Francesco who knows his abacus like a second pair of knuckles, and although we wait until it is dark, no-one comes to meet us but an escort kindly sent by the sergeant of the watch to see us back to the tavern where the dogs have scratched deep grooves in the wide oak door and left a litter of fourteen pups no bigger than a man’s thumb that the old Chinese sentries carry around under their jackets like a new heart.

Tonight they returned, no more numerous or vicious than they were yesterday, but obviously in search of their pups and the skinny old bitch that bled out on the steps of the Cathedral after bearing them. There are three young girls with a pup each here, and no-one and nothing will separate them. Pistoa has one that he holds closer than I have ever seen him hold anything, which leaves ten of the litter gone under old men’s coats to the barracks and beyond. The way those dogs are sniffing at the tavern door, though, they mean to find them.

Pistoa has often screamed for a sword when he is drunk, but this time he means the kind the Chinese confiscated in every town and village and handed back as coin to every man, woman and child. In the east the sword brandishes a sound it does not brandish here. I sleep through the worst of it, for unlike spendthrifts such as Pistoa I have money for a straw mattress and a pillow. Even the running battle he and his drunken cohorts fought with the mangy remnants of the pack up and down the narrow defiles of the sestiere did not wake me. I have a clear conscience and I grab sleep where I can find it.

Needless to say Pistoa is in no sort of mood for haggling with a fat priest the following day, so I take what I think is a fair price for his rushed work on the portico, doff my cap to a boy almost buckling under the weight of his accounts, and begin to sort the chits for the men who cannot read.

“That fat pig can’t even be bothered to see if he’s done us a favour,” Pistoa scowls as he drops those coins like watchmen’s chains into his tired sack. “You’re a priest, who was that the bells announced before?”

Sometimes I think the joke about my name has yet to wear off on Pistoa because he has suspended his judgment on it. Either he is trying to rile me like a schoolboy, or he is struggling with the urge to confess something to the last man in the world who would understand. Or working. Needless to say, it is only the latter that puts me at ease. I tell him to go look for himself, but judging by the clash of cymbals and the sad gaggle of trumpets it is someone from the east come via La Spezia, come like the rich and powerful have come since the pirates disappeared to see for themselves whether the rumours about us are true. Fat, ashen-faced men with their jowly wives and supple concubines come to lay their coins at our altars and shout their names at the impossible arches and gauge their fortunes by the number of echoes.

“Let’s go see for ourselves. Drink it down, eh priest.”

He is like this whenever one of their litters pass, be it some screw-eyed hoary scholar or a pretty merchant’s child-bride, meeting their eye with the same look he would pass over a block of stone before he begins to carve, a look the Chinese excuse because their devils are all paper and because the Carnival has this effect on some.

*

Pistoa has gone south on some vague promise of work from one of the Bishop’s men. He left with a strange halting gait and that newly-acquired bundle squirming under his jacket. Perhaps he is having second thoughts about keeping it. Second thoughts may be all those dogs were seeking inside the town that abandoned them to the winter nights and those strange creatures from the steppes. Francesco noticed Pistoa’s strange manner too, for as we headed north back to Arezzo I could feel him trying to find a way of broaching the subject without bringing down my famous curses on his head. I have only recently become aware of this reputation I have amongst the apprentices, and I am still at a loss to explain it. I speak when spoken to and find the world too changed, too changeable, to paw over the details of a brother’s walk.

I used to think Pistoa shared my feelings, but that was all a long time ago, many cold greetings ago on the road out of Dragon Pass. I now realize Pistoa is a man too constant, too wedded to his time, whatever times they may end up being, to have ever looked down and wondered whose feet they are that keep passing under him. For all his proclivities, or perhaps because of them, Pistoa is a man accepted by all and sundry, whether Christian or heathen. Perhaps because he takes the world as he finds it, and knows how to seal a contract with a day before he has even opened his eyes.

Kindling

It is not often I will agree with Louise Adler, that paean of the juste milieu in Australian publishing, and even less seldom will I publicly admit to such a strange and unwelcome confluence. But Ms Adler’s op-ed in last Saturday’s Sydney Morning Herald, Spirit of literature turns to kindling, made some interesting points about the Kindle phenomenon.

First and foremost I agree with Louise that the technology is clunky and geared toward inadvertent purchases, a common snare of this still-nascent digital age. It is also Americo-centric and lit-lite, undermining somewhat its claims to accessibility for those who, for whatever reason, cannot muster the time, energy, or inclination to step inside a bookstore.

However, nowhere does Ms Louise relate the most common complaint amongst “Kindlers”, that being that they miss the tactile pleasures of opening a book and immersing themselves in its off-white pages. Ah, the smell of a book hot off the press! Not forgetting that it is rather ill-advised to take an electronic device such as an i-pad into the bath. This omission may or may not be telling, but Ms Adler’s proposition that the established publishing industry protects the unwitting reader from dross is simply too bold a claim for this blogger to let pass. In her very own article, Adler herself is guilty of two editorial howlers – “Consequently, publishers are skeptical about partnerships on behalf of their authors’ behalf”, and “readers should be beware”. Oh dear. Once upon a time when I was still a cadet on Jones street, some wizened old sub would have swept such howlers off the table, but Louise Adler’s reputation (apparently) carries all before it, and anyway I’m not all that sure our beleaguered newspapers still carry subs.

What are your thoughts on the Kindle phenomenon? Have your say in the poll to the right.

And while we’re on the subject of editors, I have a few collective nouns to throw their way:

A shriek of teenagers

A maw of shoppers

A patchouli of hippies

A spleen of Kiwis

A sulk of poets

A scorn of Poms

A sulk of poets

A scorn of Poms

A pedant of Justins

Feel free to add to the list.

New Writing by Wayne H.W. Wolfson

It is going to rain, which is all right as it’s the end of the day and I had planned on spending the night reading Racine. The one cloud which carries the storm is a giant, slow moving beast who takes all of dusk to crawl across that of the sky which is visible between my building and the one opposite, where earlier when it had still been hot I had seen a girl. The same one who I always managed to become an unintentional voyeur of.

Today was different, she was clad only in her underwear, phone cradled between cheek and shoulder, slicing a cantaloupe. There was an odd symmetry that the French windows of my bedroom lined up with those of her kitchen.

I had seen her often in clothes that appeared comfortable and surely were reserved for wearing only around home. The thin off white robe which went well with her mocha skin, drawstring pants whose legs sometimes got stuck in the top of her socks, a faded tee shirt that was now gray and might once have been black.

Naked, I saw a little belly which showed that, like me, she believed a little pleasure at the table was nothing to worry about. Her breasts were pendulant, swinging as she bent down without dropping the phone, for something out of view.

Twice her hands absent mindedly wandered towards her nipples which were dark and erect. She smiled but quickly moved them away as if receiving an electrical shock.

What ever dish she had been preparing was ready, she suddenly arched her back for a moment and then quickly left the room. I do not know if she saw me and I wondered what she would look like tomorrow.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)